Engagement increases respect, appreciation, and partnership between journalists and communities.

In 1775, the American Revolution launched an experiment in engagement called “democracy”. That sparked a critical need for an informed public and ignited a mass literacy movement.

In 1775, the American Revolution launched an experiment in engagement called “democracy”. That sparked a critical need for an informed public and ignited a mass literacy movement.

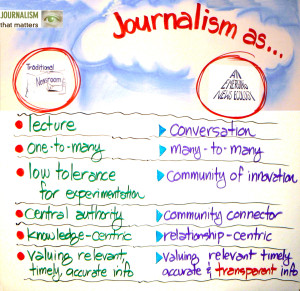

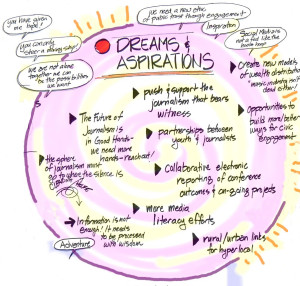

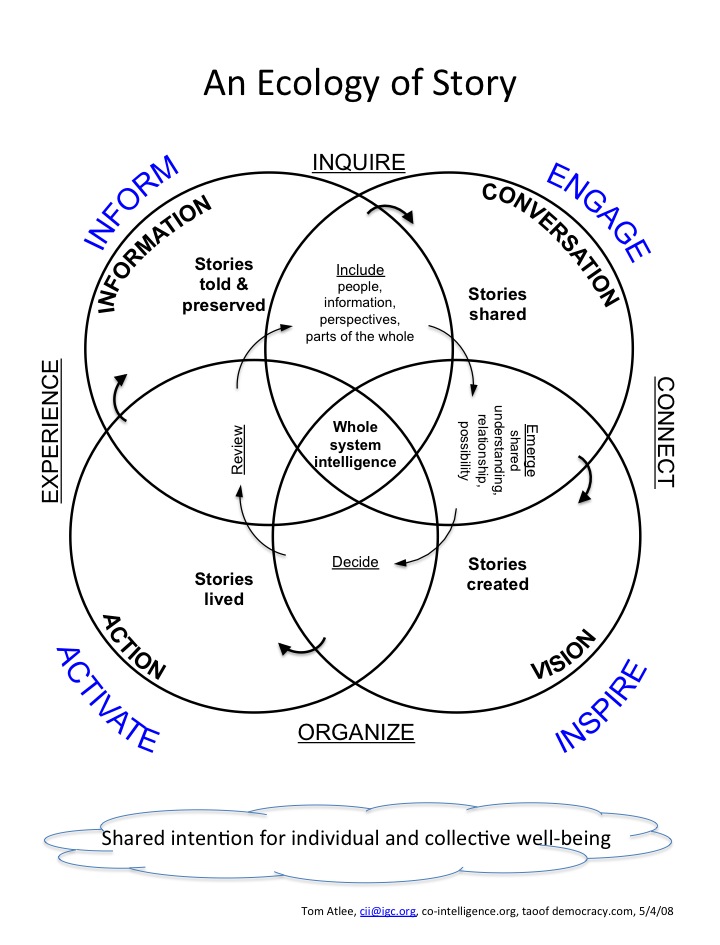

Today’s technological wonders are generating a “media literacy” movement that is fueling a new level of engagement. Journalism is no longer a one-way communication from journalist to audience. It is a conversation. News and information is created, published, curated, used, archived, influenced and more by anyone. And many use social media to communicate and make meaning from news and information with friends, family, interest groups, and strangers.

As the founders knew when they shaped the First Amendment to guarantee free speech and a free press, engagement is essential to democracy and to vibrant community life. As Reynolds Journalism Institute Fellow, Mike Fancher, puts it, public trust grows through public engagement.

The Lawrence Journal World’s WellCommons.com, is a great example. Its chief architect, Jane Ellen Stevens invited the public to help define it. According to Stevens, they set a goal to be the go-to place for news and information on health and wellbeing in the region. Half of the content comes from community members and half from professional reporters. The site has changed the community’s conversation about health and caused a more solutions-focused style of reporting.

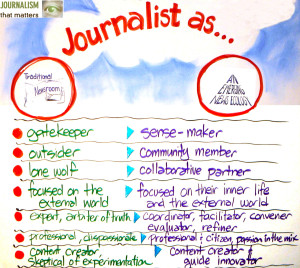

Like many other professions, journalists are renegotiating their roles and responsibilities as professionals. Among the new roles: community hosts, data wranglers, and beat bloggers. Consider some shifts in who provides content:

Personal storytelling. Schools, libraries, and even journalism organizations are teaching skills to the public to help them discern quality, reliable content and to support people in creating their own stories. For example, through the “Living Textbook”, Arab American seventh graders learn journalism skills and tell stories about identity and how they see the world.

Personal storytelling. Schools, libraries, and even journalism organizations are teaching skills to the public to help them discern quality, reliable content and to support people in creating their own stories. For example, through the “Living Textbook”, Arab American seventh graders learn journalism skills and tell stories about identity and how they see the world.

Community and organizational storytelling. With fewer professional journalists, communities and organizations are taking charge of their stories. For example, the Colorado Health Foundation created the Colorado KaleidosCOpe, a “statewide storytelling campaign designed to shine a bright light on the good work of our grantee partners and the people whose lives they impact.”

Professional journalistic storytelling. Professionals still contextualize, deepen and amplify stories. They can tell complex stories that take dedicated research and do the analysis and communication to help tackle tough subjects. They can help us make sense of the overwhelming amounts of information by showing us patterns and trends that shape society.

Because of these shifting roles and cultural changes, both journalists and the public they serve are asking a key question:

What is newsworthy?

No longer solely controlled by journalists, how shall we –journalists and the public – discern what stories are critical for our communities and democracy? Journalists want to be relevant and trusted. The public wants important and trustworthy information. Imagine a full partnership: journalism of, by and for the people. That requires engagement. The principles that follow speak to how to make that happen, where you are in the system.

Tips for Engaging

Whether online or in face-to-face conversations, some strategies to remember:

- Invite the people who care about the issue, then welcome who and what shows up.

- Ask real questions — meaningful ones for which you don’t know the answers and are genuinely curious.

- Make it simple and easy to get involved. Consider accessibility. In person, handle parking and daycare. Online, be crisp, brief, and able to participate with one click.

- Make it fun. We’re more creative and collaborative when having a good time. In person, have food.

- Make space for individual expression and connection with others. We all crave to be authentic and to belong. Support both.

- Work in cycles. Offer context and a question. Invite a response. Feedback or reflect together on what you learn, likely triggering another cycle.

- Treat disruptors with compassion and respect while being firm and clear about appropriate behavior. They likely have something important to contribute but lack the skills to communicate it. Welcome the message while handling bad behavior.

Just as engagement is key for successful system change, diversity fuels innovation and a sense that we’re all in it together. Stay tuned for more in the next post.

In the spirit of sparking engagement: enter a word or phrase on how you decide what is newsworthy in the comments below.

Got something to contribute?

A tip? An article? I’ve started gathering resources. Please add by

- Posting on the JTM Facebook page

- Joining the JTM Google Group

- Commenting on this post (below)

- Emailing me

Unless you explicitly request otherwise, I will post comments sent via any of the above in the comment space below.

=======

Read the other posts in this series:

- What do we need from Journalism?

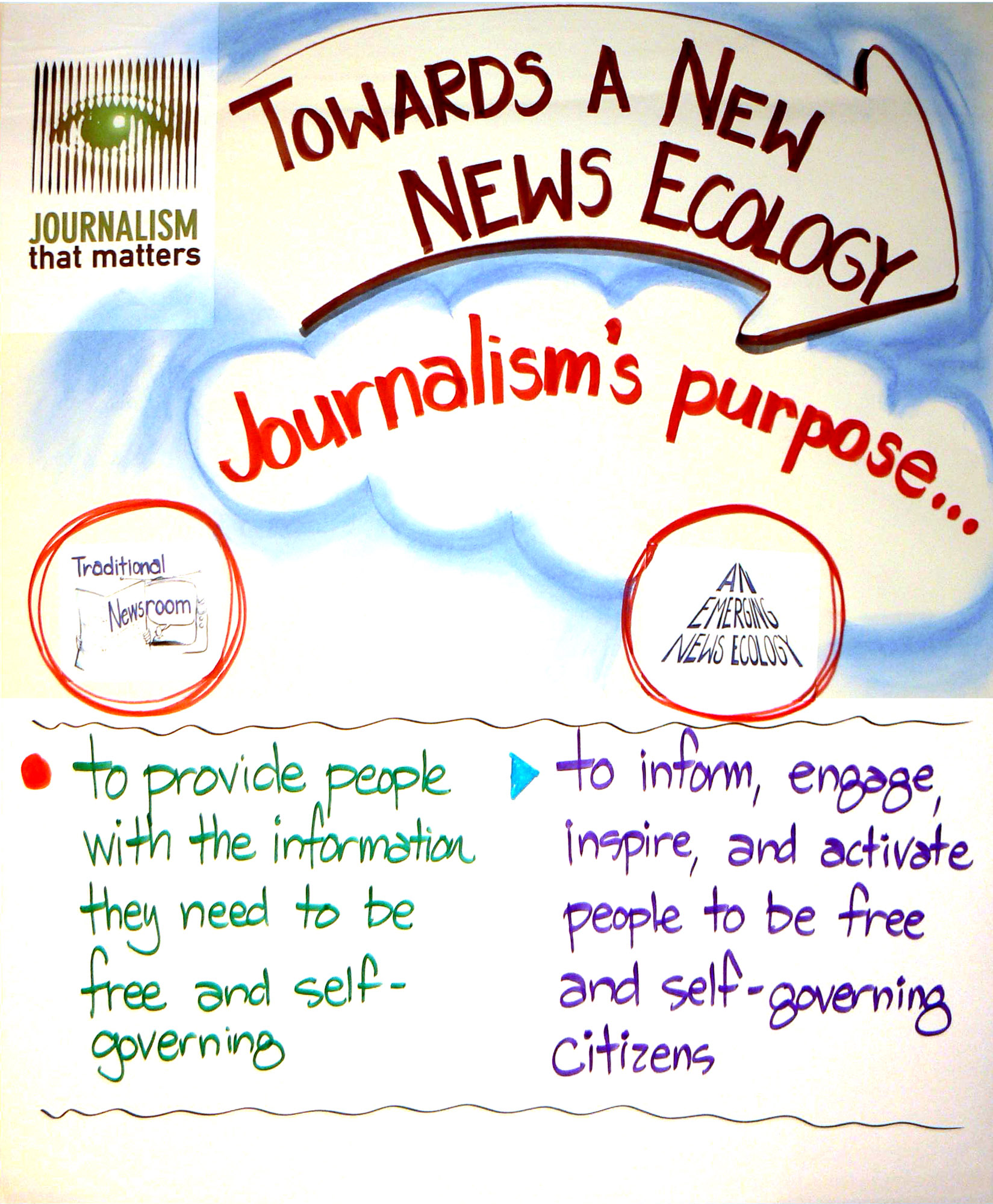

- An Expanded purpose for Journalism

- Journalism for Navigating Uncertainty

- The Possibility Principle

- The Engagement Principle (this post)

- The Diversity Principle

- The Changing News & Information Ecosystem: What can you do?

- Mapping the News and Information Ecosystem

Possibility-oriented stories generate new options. Research on the relationship between

Possibility-oriented stories generate new options. Research on the relationship between

My perspective comes from thirteen years of working with journalists through

My perspective comes from thirteen years of working with journalists through