The following article appeared in the Sprint/Summer 2009 issue of Kosmos

It reflects the themes that surfaced through the many conferences. Since then, additional themes include:

- Journalism is still about the public good; and now it is entrepreneurial

- Small organizations bring heart. Large organizations bring credibility. Collaborate!

- Communities can take responsibility for their own narrative. One strategy: embed journalists in the community

- Librarians and journalists share common cause for engaging the public in civic life.

- In the digital age, news and information will look as different from newspapers, TV, and radio news, as these innovations did when pre-printing press, news was delivered from the pulpit. Think investigative journalism delivered via hip hop and video games.

******************

Journalism that Matters:

An Emerging Cultural Narrative

by Peggy Holman

What does it take to change a social system, an industry? Like journalism…

For nine years, Journalism that Matters (JTM) has:

* Invited people from all aspects of journalism: print, broadcast, and new media; editors, reporters, bloggers, audience, reformers, educators, and others;

* Created space for conversations among peers about what matters most to them;

* Worked at the emerging edge of the new news ecology.

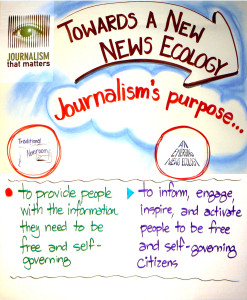

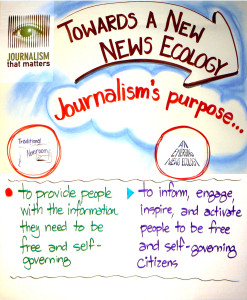

We have witnessed a new story of journalism being born as the old story is dying. At its heart, that new story stays true – and enlarges on – a purpose many journalists hold dear: “to provide people with the information they need to be free and self-governing.” (Kovach and Rosenstiel, 2001)

The Beginning

For me, Journalism that Matters started with an act of violence. In 1999 a mass shooting happened at a Jewish Community Center in Los Angeles. I was working with Appreciative Inquiry, a process based in the idea that positive action follows positive images. In other words, stories of danger make us hunker down, while stories that illuminate possibilities inspire and activate us. I thought, “the stories we are collectively telling ourselves, through journalists, are not serving us well.”

A friend introduced me to Stephen Silha, a free-lance journalist. Stephen connected us with Chris Peck, incoming president of the Associated Press Managing Editors. During our first conversation, Chris asked an ambitious question:

“What would it take to have a national conversation about the future of journalism?”

Stephen, Chris and I created a plan. We were subsequently joined by Bill Densmore, of the Media Giraffe Project. While it has unfolded completely differently, Journalism that Matters has convened twelve conversations among more than 800 people from the evolving ecosystem of journalism.

Since we began, technology has radically altered the nature of our communications. The Internet enables anyone to publish, shaking old assumptions of who is a journalist and what constitutes journalism. Social networking technologies such as Facebook ushered in an age of many-to-many connecting. We no longer depend on a few publishers and broadcasters to set the collective agenda. More than passive recipients of information, we are now active participants shaping our cultural narrative.

For generations, newspapers — and then television — gave us the news, telling us what needed our attention. As we became “consumers” of news, the stories began to change, no longer providing what we needed to know as citizens. Perhaps, this, as much as changing technology, has created a generation that finds no connection between journalism and democracy. For many under 40, the information they need to be engaged citizens does not come through traditional journalism. As aggregators like Google News use algorithms for choosing what stories matter, our cultural narrative arises from what we collectively follow. So newspaper circulation and ad revenues decline, and broadcast news viewers age (think ads for Viagra and Boniva for bone loss). Does this decline threaten the health of democracy? Or has journalism as we know it passed its time?

Journalists struggle to understand their changing role in a context where anyone can publish, people engage each other about what matters to them, and technology aggregates the agenda. The rest of us struggle with shifting from consumers to co-creative citizens. Though it will be a while before we have a clear picture of journalism’s new story, its role in democracy, and our role in it, many exciting experiments give us clues to that future. Through JTM we are learning about

* the essential purpose of journalism,

* the nature of storytelling,

* who is involved,

* how it is practiced,

* how it is taught, and

* how it is financed.

The Essential Purpose of Journalism

If journalism’s old story was to provide people with information they needed to be free and self-governing, in the emerging story, journalism not only informs, but engages, inspires, and activates people to play their roles as free and self-governing citizens.

The nascent beginnings of this expanded purpose are visible through “place bloggers”, online sites providing community news, information, and electronic conversation spaces in which residents exercise the muscles of civic engagement. People share their stories. They see connections with local governance and with each other. As the hosts of these local communities meet – as they did at JTM’s 2008 Minneapolis gathering (www.newpamphleteers.org), they make connections that re-knit the fabric of democracy from the grassroots out, feeding our larger sense of nation-as-community and even world-as-community. No longer a one-way communication from journalist to audience, journalism sparks community conversation. This changing role reveals some new characteristics of journalism:

| TRADITIONAL NEWSROOM |

NEW NEWS ECOLOGY |

| Journalism as… |

| lecture |

conversation |

| central authority |

community connector |

| knowledge-centric |

relationship-centric |

| one-to-many |

many-to-many |

The Nature of Storytelling

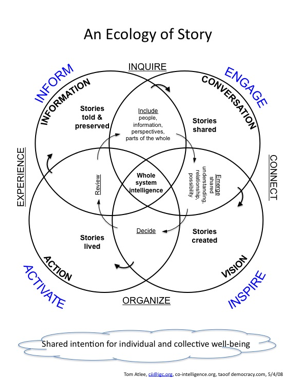

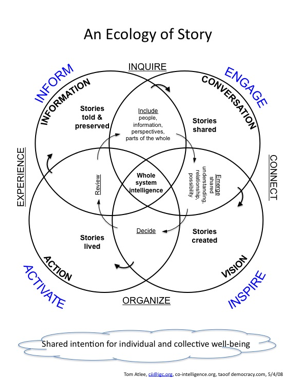

If journalism has an expanded mission – to inform, connect, and inspire action — then the nature of journalistic storytelling itself is changing. Tom Atlee of the Co-Intelligence Institute offers a model that, among other things, can help assess the likely effectiveness of a story or a news organization by asking:

* Does it inform? (a primary focus of traditional journalism)

* Does it engage? (a primary focus of the social networking)

* Does it inspire? (almost virgin territory, but hinted at by the idea of “possibility journalism” described below)

* Does it activate? (almost untouched terrain)

* Is it part of a process that facilitates collective learning-from-experience by the community? (integrating all aspects as a cycle)

The Sixth “W”

What is possible now?. An example of “possibility journalism” emerged from a project launched following JTM-Kalamazoo, called the Common Language Project (CLP), www.commonlanguageproject.net. CLP puts a human face on complex, international stories. Sarah Stuteville, JTM alum and CLP co-founder offers this story:

I was in the Middle East talking with a Palestinian about frustrating, polarizing material. He kept repeating the same ideas over and over so I asked that magic question: “given what’s happening, what’s possible now?” It shifted the interview completely, as our contact began envisioning the situation in a completely new way.

By adding “What’s possible now” to the traditional five “W’s” of journalism – who, what, when, where, why, and how — stories call forth hopes and aspirations.

Who is Involved

At JTM-Washington, DC (www.mediagiraffe.org/wiki/index.php/Jtm-dc) there were fierce conversations between long-time journalists and newcomers. One journalist had a change of heart about “citizen journalists” when their conversations made clear that the primary difference between pros and serious amateurs were (1) who gets paid; and (2) professionals COVER stories, citizens SHARE THEIR stories.

Journalists are no longer gatekeepers to the stories that matter, though many have been so busy guarding the gate that they have not noticed the fence is gone. Still, with the vast increase of sources, the role of making sense of a complex and rapidly changing world is more vital than ever. And the range of options for receiving and making sense of news has exploded, becoming more confusing in the process. Traditional sources — newspapers, television, and radio — are supplemented by blogs, video blogs, and Internet radio. Sense-making often occurs through conversation, as social networking sites and local platforms for civil discourse support fact-checking and collective meaning-making.

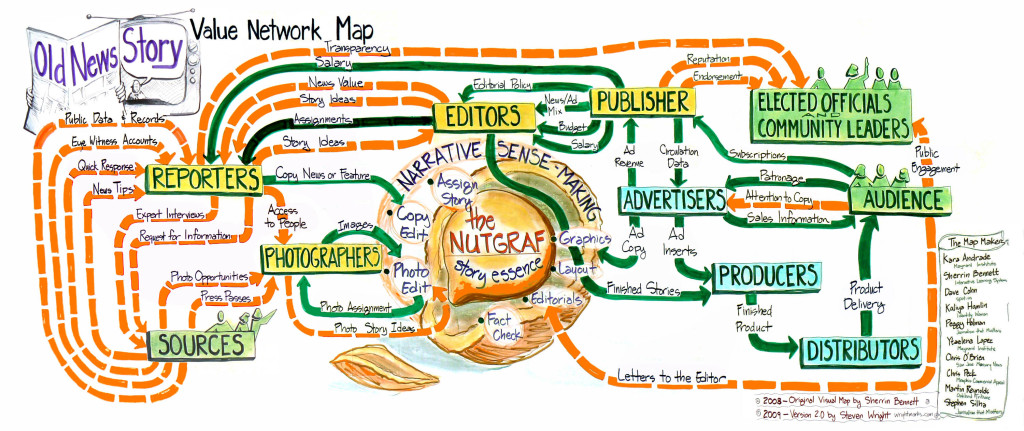

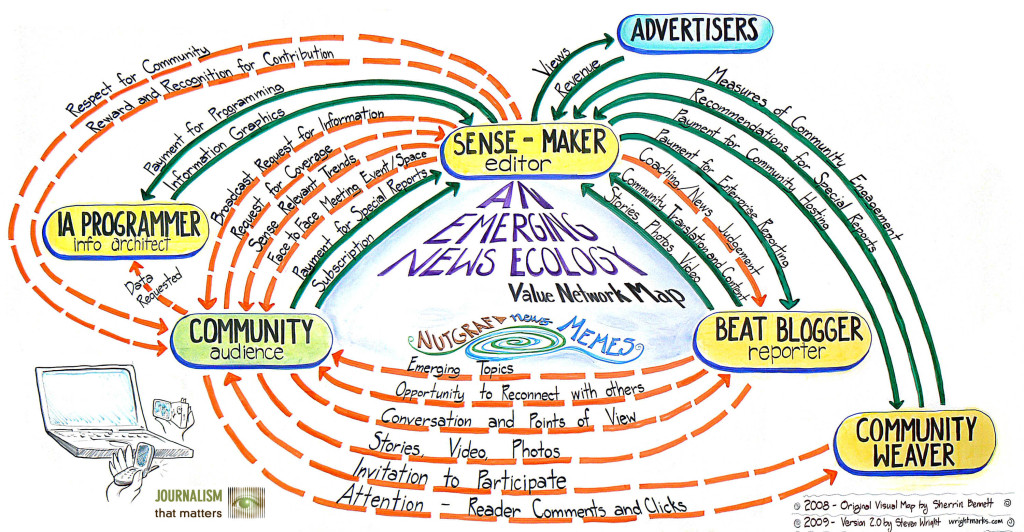

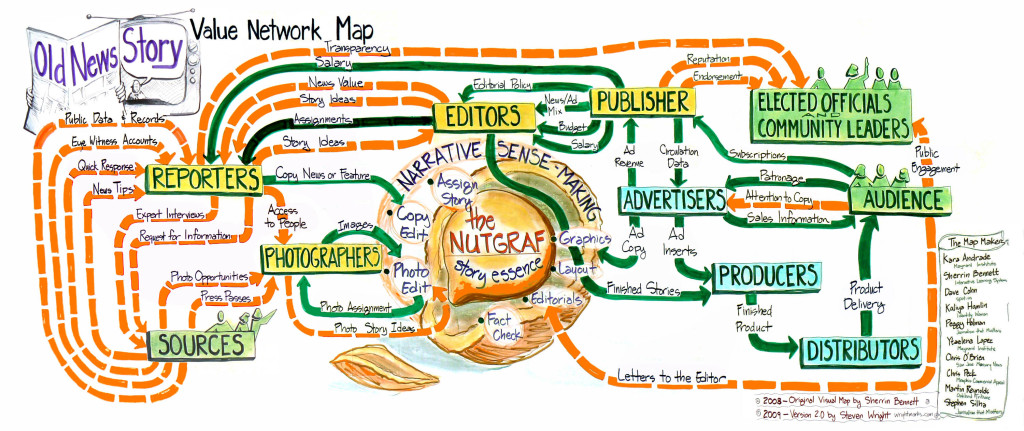

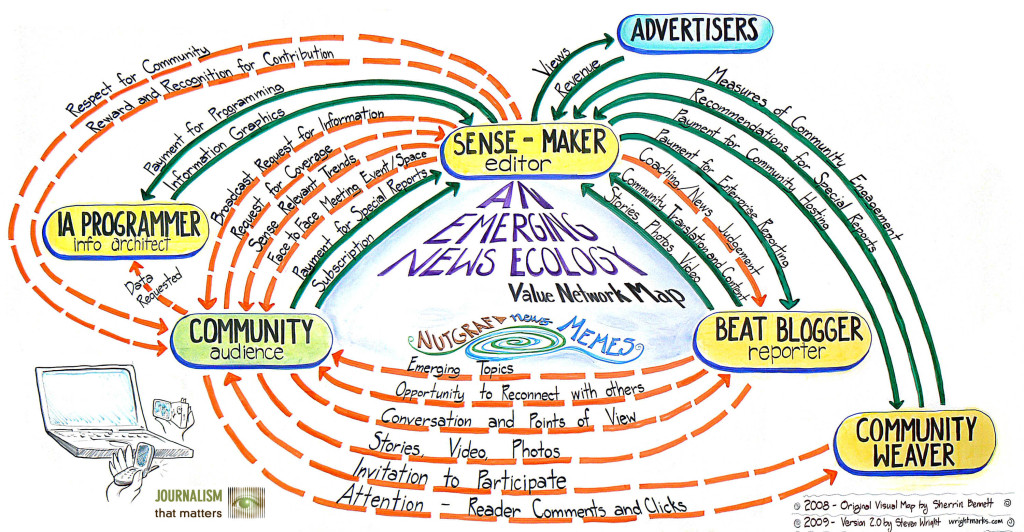

For JTM-Silicon Valley (www.newstools2008.org), which brought together journalists and technologists, two maps were created: 1) the primary roles in a traditional newsroom and 2) a preliminary sketch of emerging roles.

We began the emerging news ecology map with three roles: community, beat blogger, and sense-maker. Given the growing emphasis on conversation, “community weavers” skilled at hosting civil online (e.g., www.westseattleblog.com) and face-to-face conversations were soon added. These roles are clearly just the beginning.

How Journalism is Practiced

Virtually every aspect of journalistic practice is changing, with self-publishing, 7×24 coverage, social networking, crowd-sourcing, Twitter, blogs, mainstream outlets, and more. Multi-media reporting skills become essential as stories are distributed via computers, cell phones, and iPods. As distribution goes “high tech”, sourcing stories goes “high touch”. Public radio’s Public Insight Journalism engages ordinary people to cover news in greater depth and uncover stories not otherwise found (www.americanpublicmedia.publicradio.org/publicinsightjournalism).

No longer are events the only trigger for a story. For example, JTM alum, Ilona Meagher (www.niu.edu/PubAffairs/RELEASES/2007/aug/ilona.shtml), unexpectedly found herself an expert on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder because she started writing about the interconnections she uncovered by researching a subject important to her. Now she is in journalism school, learning the craft that adopted her.

More people are involved in telling stories today. Tapping into networks of bloggers to bring complex stories into focus as “beat bloggers” (www.beatblogging.org) do, journalists move from outside the system to being key connectors within a system.

| TRADITIONAL NEWSROOM |

NEW NEWS ECOLOGY |

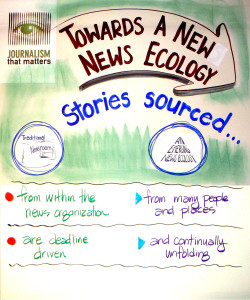

|

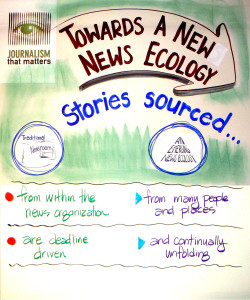

Stories sourced… |

|

|

| from within the news organization |

from many people and places |

| from events |

from events and noticing emerging patterns |

| are deadline driven |

are continually unfolding |

|

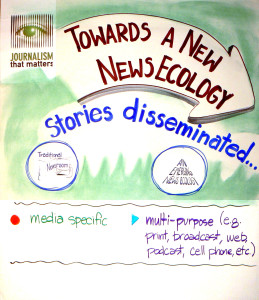

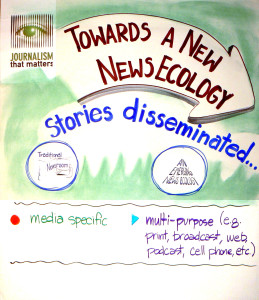

Stories disseminated… |

| media specific |

multi-purpose (e.g., print, broadcast, web, podcast, cell phone, etc.) |

|

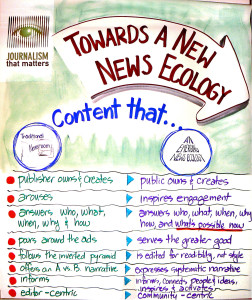

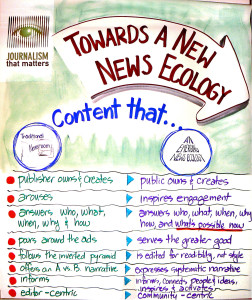

Content that… |

| publisher owns and creates |

public owns and creates |

| answers who, what when, where, why and how |

answers who, what when, where, why, how, and what’s possible now |

| pours around the ads |

serves a greater good |

| follows the inverted pyramid |

is edited for readability |

| offers an A vs. B narrative |

expresses a systemic narrative (A relates to B, influenced by C, contextualized by D, E, and F) |

| informs |

informs, connects people and ideas, inspires, and activates |

| editor-centric |

community-centric |

| arouses |

inspires engagement |

|

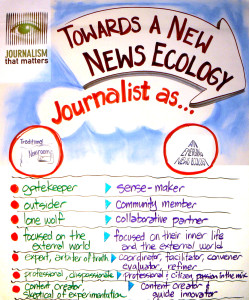

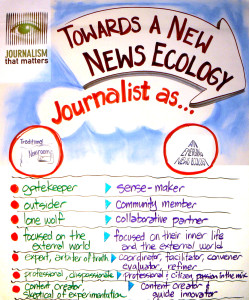

Journalist as… |

| outsider |

community member |

| gatekeeper |

sense-maker |

| focused on the external world |

focused on both inner life and external world |

| expert, arbiter of truth |

coordinator, facilitator, convener, evaluator, refiner |

| professional, dispassionate |

professional and citizen, passion in the mix |

| content creator |

content creator and guide |

| skeptical of experimentation |

innovator |

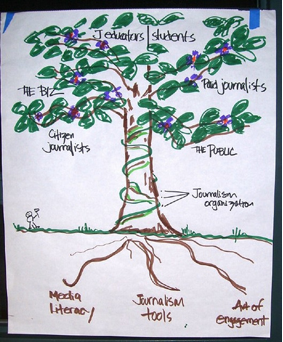

How Journalism is Taught

How do you prepare a new generation when the field is radically changing? Some exciting insights emerged at JTM-DC, captured by Dale Peskin:

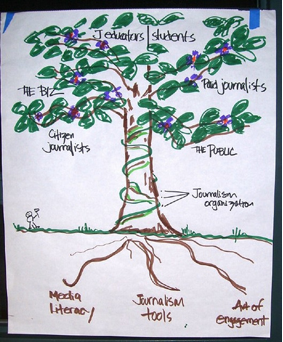

Of particular interest are the three roots:

* broad-based media literacy

* journalism tools, including traditional craft and values, and emerging values and skills, such as transparency and multi-media reporting

* the art of engagement – convening community both online and face to face.

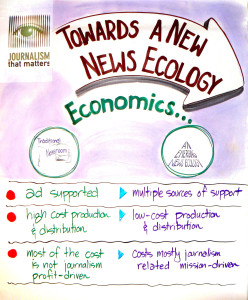

How Journalism is Financed

Likely last to emerge will be a viable economic model. Among the ideas and experiments:

* Community-supported journalism (e.g., community radio, Democracy Now)

* A utility model (funded as a basic service, like water and power)

* Community-owned (every citizen has shares and citizens retain oversight authority)

* Crowdfunding: JTM alum, Dave Cohn, funded by a Knight Challenge Grant created www.spot.us, “that allows an individual or group to take control of news in their community by sharing the cost… to commission freelance journalists.”

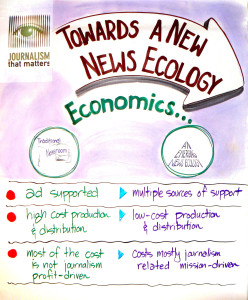

Changes to the economics include:

| TRADITIONAL NEWSROOM |

NEW NEWS ECOLOGY |

|

Economics… |

| ad supported |

multiple sources of support |

| high cost production and distribution |

low cost production and distribution |

| most of the cost is not journalism |

costs mostly journalism related |

| profit-driven |

mission-driven |

Open Questions

Two important questions for deeper exploration in JTM conversations:

How do we engage an increasingly diverse audience? And how do we ensure investigative journalism – community, national, international – is done well?

I now believe that journalism is too important to be left solely in the hands of professionals. Even as journalists struggle with their new role, it is up to us citizens to determine our place in the new media landscape. Ultimately, the emerging news ecology will serve its purpose well only by answering the question:

How can journalism inform, engage, inspire, and activate us — materially, intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually — to be free and self-governing citizens and communities?

Bibliography

Kovach, Bill and Tom Rosenstiel, The Elements of Journalism. Crown Publishers, New York, 2001, p. 12.

Thanks to Steven Wright for the visual recording.