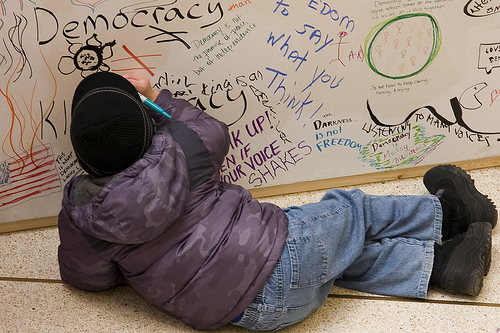

Imagine if a newspaper white-washed the side of its building every morning and encouraged strangers to tag it with their response to the day’s news. Now imagine that printed in each edition of this paper is a photo of that wall just before it was painted over again.

Although the experiment might yield interesting results, most of the messages on the wall would probably do little to contribute to the conversation about the news of the day and much of it would be little more than graffiti.

Without moderation, comment sections on news Web sites quickly become like that wall, but real conversations are possible when news organizations invest the time to manually curate their comments and foment discussion.

Managing online comments can be a challenge for any news organization, but as Poynter veteran Butch Ward points out in a recent column, the solutions are simple but are resource intensive.

Which brings us back to those cursed Web comments sections. What can be done to make more of them places for productive debate?

Three ideas I hear most often are these:

- Comments need to be moderated.

- Comments sections need to be more than fenced-off areas for the public to talk among themselves. They need to be part of a newsroom’s coverage strategy.

- Reporters and editors need to participate in the conversation.

For starters, moderation. Conversations on websites that moderate comments tend to be more substantial and less venomous. So why aren’t more comments sections moderated?

Money, of course. Many newsrooms have decided they don’t have the resources to invest in good comments sections. A few are “deputizing” members of the public to police comments, and the verdict is still out. The others? Well, as my mother would say, you get what you pay for.

The Illuminations Blog previously looked at how newspapers are using services like Disqus and Facebook to require commenters to use their real names. But this low-cost solution pales in comparison to the power of human intervention transforming a discordant sea of ad-hominem attacks into a meaningful forum filled with civil discussions.

Sandy Heierbacher, the Director of the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation, has been looking at civility in online comments and has identified a few local news sites willing to make the investment needed to maintain it.

“I think Deseret News is a really interesting example of a newspaper that took charge of the incivility in its comments,” said Heierbacher in an e-mail. “And I really like this gritty 2010 article on wordyard.com, which points out that platforms like The Well have decades of experience with online commenting. It also emphasizes that it’s not just about moderation.”

Deseret News is a newspaper serving the Salt Lake City, Utah, area. Most of the stories on the front page show only a handful of comments, but because the comments must be approved before being posted to the site its unclear how many might be in the queue. The most commented story listed on the front page has 106 published comments, which reveal an incredibly civil discussion over gay marriage — for a newspaper comment section — which I imagine is particularly controversial within the newspaper’s coverage area.

In the wordyard.com article Scott Rosenberg writes that although it isn’t a bad idea to require commenters to use their own names, it’s all but impossible to enforce and won’t prove very effective if the environment has already turned vile.

“Show me a newspaper website without a comments host or moderation plan and I’ll show you a nasty flamepit that no unenforceable ‘use your real name’ policy can save,” writes Rosenberg. “It’s often smarter to just shut down a comments space that’s gone bad, wait a while, and then reopen it when you’ve got a moderation plan ready and have hand-picked some early contributors to set the tone you want.”

The San Francisco Bay Guardian did exactly that last August. The newspaper closed comments for a one-week period and offered an in-person forum as a substitute for the one online. Although the trolls quickly returned, a visit to the site this week reveals a far more civil environment than it seemed to be a few months ago.

“It’s hard to assess what impact my decision to temporarily suspend comments had, but I do feel like it was a shot over the bow of those who use our comments solely to undermine the work we do,” said Editor Steve Jones. “With new leadership at the Guardian, they seemed to realize that they’d lose their forum if they didn’t clean up their acts a little. It didn’t change much, and we are still planning to implement a comment registration system.”

Publisher and Web Editor Marke Bieschke said in an e-mail that he’s increased his efforts to remove comments that violate the site’s policy but also pointed to troll cannibalism as one reason for the increased civility.

“I know a couple of our most notorious trolls seem to have been hounded off the site by other trolls,” said Biescke.

But perhaps if Biescke had the resources to take advantage of Ward’s third point in his Poynter article — reporters and editors need to participate in the conversation — then his staff might have been able to transform the trolls into healthy contributors or at least persuade them to spew their venom elsewhere.

“Talk about a hard sell,” said Ward. “The truth is, most journalists have never been anxious to mix it up with the public. Newspaper editors and reporters for years responded to unhappy readers with one, or both, of these scripted responses: ‘We stand behind our story,’ and ‘Why don’t you write a letter to the editor?'”

Ward goes on to publish an interview he conducted with two journalists from the Financial Times. But one thing that may make comments posted at the Financial Times distinct from those being left on the Bay Guardian’s Web site or most other publications is that the site lives behind a pay-wall making its comments only accessible to paid subscribers. This certainly diminishes the number of trolls, which I’d imagine are already greatly reduced given the site’s specialization.

I’ve often wondered what would happen if general-news sites like the Huffington Post reserved comment privileges to paying members, but I doubt many would pay for that opportunity alone. Without a layer of curation beyond simple moderation, it would be overwhelming for reporters try to engage with the several hundred comments that can pile up on a popular story.

The Verge, a technology news-site based out of New York has somehow inspired its staff to not only engage with the comments on their own articles but also those written by their colleagues, but the site is one of a few exceptions I’ve found.

Gawker Media is another site where its contributors regularly participate in the comments. The threads in which the author has joined the conversation are marked off with a star and the words “Author is participating” are affixed to a banner on the top. The company has also made a concerted effort to elevate reader comments and participation by creating Kinja, a sort of personal publishing platform for Gawker content.

Kinja users are given a URL where they can curate pages from Gawker sites while also compiling any comments posted by the user. The potential for Kinja was revealed in October when Linda Tirado wrote a lengthy comment about poverty that went viral on her Kinja account Killermartinis. That comment eventually generated over $60,000 in donations and a likely-unpaid position as a contributor for the Huffington Post.

While the Huffington Post maintains a line between its contributors and its commenters, it has certainly tapped its audience to contribute and remains a mixture of professionally produced and unpaid content. Sites like the Daily Kos and Buzzfeed have gone even further in incorporating user-generated material into their strategy. Both sites provide a platform for users to generate their own content that they can promote themselves but is also sometimes highlighted alongside the work of their paid staff.

Comments have been a key component to online publishing almost since its inception. For much of that time comment systems have seen little nurture and almost no new development and online conversations have suffered as a result. As more and more attention is paid to rethinking online commenting, new tools are quickly emerging that promise to bring relief to the pains associated with online conversations. But no amount of engineering will ever replace the human resources needed to keep that conversation both civil and engaging.