With rare exceptions, advertising is the lifeblood of a sustainable news enterprise. When reduced to its simplest terms, a news outlet’s business model can be broken down to selling advertisers access to an audience.

This is the same business model that catapulted Google to become one of the most profitable companies on the planet, and it is the same business model that is now affording Facebook financial success and made the upcoming Twitter IPO possible.

If advertising is generating billions of dollars for these online ventures, why is the news business in such dire straits and starving for revenue? While it may not be feasible for a single news organization to bring in the $950 million of advertising revenues that Twitter projects for the upcoming year, there remains an opportunity for both the established and emerging news industry to reclaim more of those advertising dollars that once kept newsrooms filled with reporters.

Throughout the journalism community there is a near consensus that the future of journalism depends on sources of revenue outside advertising. Last year, when the Tow Center Center for Digital Journalism released its report, Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present, Journalism in the Americas reported it on their Web site with this headline: The ad-based journalism industry is dead, says Columbia University in new essay.

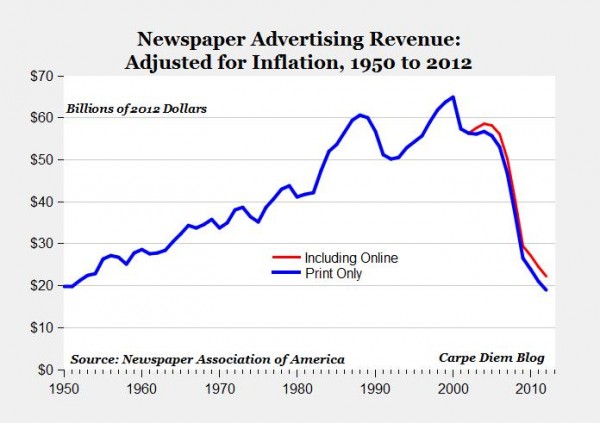

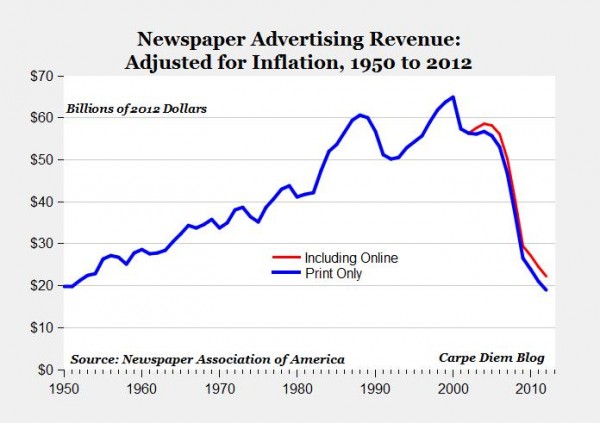

The amount of money spent in newspaper advertising grew steadily throughout the 20th century, peaking around the year 2000 with nearly $65 billion in annual revenue. It has sharply declined ever since. By 2012, the total revenue across the industry had plummeted to $18.9 billion, according to the Newspaper Association of America.

The amount of money spent in newspaper advertising grew steadily throughout the 20th century, peaking around the year 2000 with nearly $65 billion in annual revenue. It has sharply declined ever since. By 2012, the total revenue across the industry had plummeted to $18.9 billion, according to the Newspaper Association of America.

The decline of advertising does chart the growth of Craigslist, which went online in 1996 but didn’t expand to other cities until the summer of 2000. While it’s possible that newspapers had an opportunity to generate some revenue by launching their own free classifieds marketplace before Craig Newmark arrived, the nature of the internet and online bulletin boards all but ensured the death of revenue through classified ads.

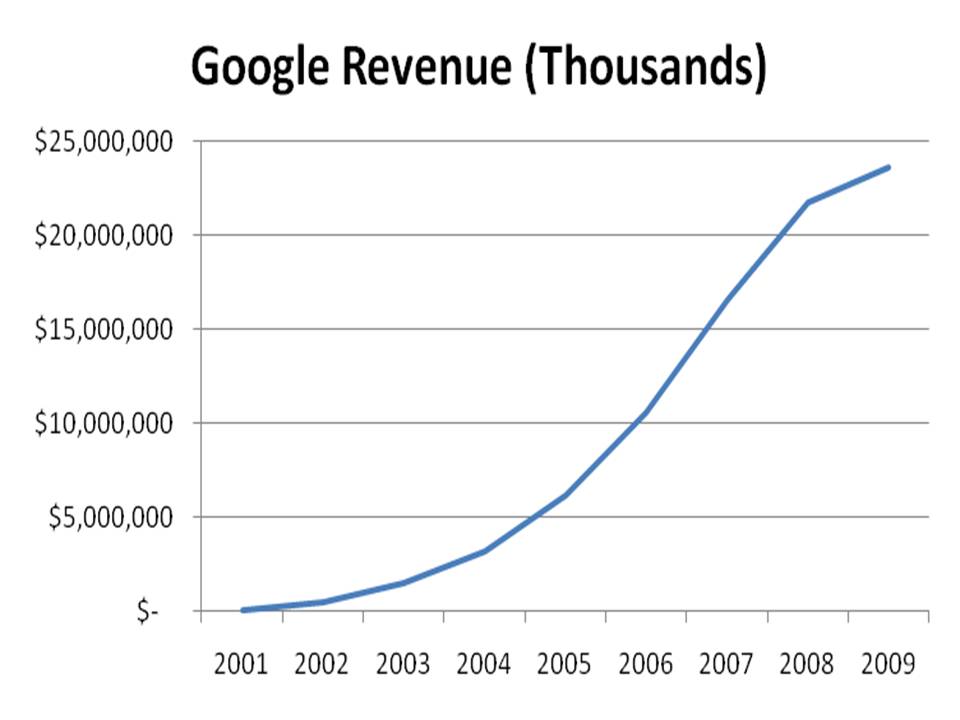

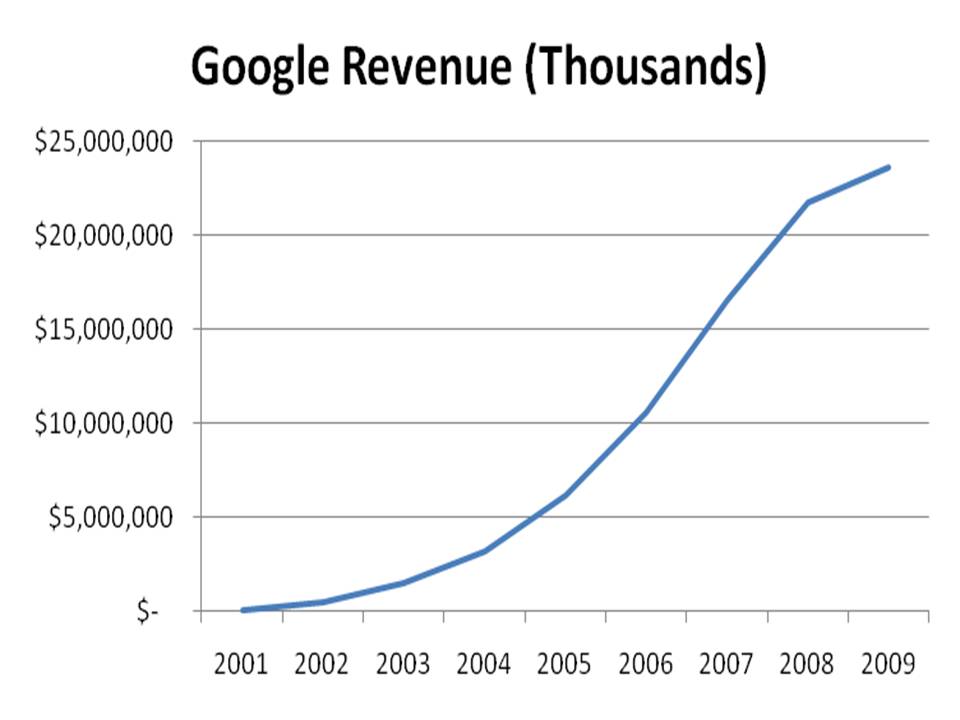

The year 2000 was also when Google began selling advertising, something that its founders had decreed as “inherently biased toward the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers,” in an academic paper the duo had written two years earlier. But by 2006, the company reported nearly $10.5 billion in advertising revenue, and even today the vast majority of the company’s $50 billion in annual revenue comes from advertising.

The year 2000 was also when Google began selling advertising, something that its founders had decreed as “inherently biased toward the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers,” in an academic paper the duo had written two years earlier. But by 2006, the company reported nearly $10.5 billion in advertising revenue, and even today the vast majority of the company’s $50 billion in annual revenue comes from advertising.

It would not be wise for a news organization to compete against Google with its own search engine, and I don’t think any have tried. But not all of that advertising is displayed alongside search results. Thousands of Web sites are sharing advertising revenue with Google by using Adsense to serve up ads all over the web; YouTube advertising works in a similar fashion.

Though it’s probably too late for the news industry to translate its long-standing relationships with advertisers into an advertising network comparable to Adsense, there remains opportunities for advertising deals that can provide media organizations stronger revenue than the 68% share offered by AdSense.

Facebook launched in 2004, but the site didn’t open it’s doors to the general public until September 2006. Last year the company reported $5 billion in revenue and about 85% of that money comes from advertising. While Facebook has struggled to generate the advertising necessary to maintain a healthy profit and demonstrated its performance on the stock market following the company’s IPO last year. The stock lost a quarter of it’s starting value within a month of going public, but it has been gaining ground over the last few months as advertising revenue has improved.

Have you started seeing Facebook posts in your Timeline that only revealed themselves to be sponsored content after careful inspection? While Facebook ads once lived off to the right side of the screen where you could safely ignore them, the company has since embedded them into the Timeline in such a way that the only giveaway that the post wasn’t shared by your friend are the “suggested post” at the top and “sponsored” printed underneath in a subtle gray.

By creating an advertising product that seamlessly blends with the rest of the content, Facebook has finally developed a new way to sell companies access to its growing audience. The site also encourages its users to like commercial endeavors including movies, music and even companies that can harness this network to deliver a more personalized — and monetarily valuable — experience.

Not only that, but the company also offers another way to give their advertising clients better access through Facebook Exchange. The service allows advertisers to monitor your activities on the Web so that it can deliver advertising for products you were already looking at. Though the first time I noticed an advertisement for something I had just been reading about, it felt like kismet and that’s exactly why the service is appealing to advertisers.

Now Twitter is readying its own IPO and is expending tremendous resources to find a way to generate enough revenue to satisfy investors. Twitter is projecting $900 million in revenue for 2014, but even after generating $422.2 million in revenue during the first nine months of this year, the company still lost a total of $133.8 million. Still, if it can follow the trajectory of Facebook and Google before that, the company stands to begin making a profit soon.

There are many things that differentiate these three companies from all content-creating news organizations; the first, obviously being the creation of original content. Since Google, Facebook and Twitter are each content aggregators as well as platforms for user-generated content, the companies avoid most of the expenses of hiring an editorial department.

Because there are no established ethical boundaries prescribing how advertising should function in this emerging form of media, approaches that blur the lines between content and advertising are sometimes embraced. These new forms of advertising raise ethical questions around privacy and disclosure, but they also work to convert sales and are generating significant revenue. Revenue that news organizations may need to stay alive as other advertising revenue continues to diminish.

Following the path carved by Buzzfeed and other digital upstarts, traditional media is increasingly turning to sponsored content to generate revenue, concluded a July report by Edelman, a PR firm. But the increased revenue can have its price, as an embarrassed Atlantic learned when it ran unwise sponsored content provided by the Church of Scientology back in January.

For Adage, Michael Sebastian reports:

For marketers, the appeal is simple: Audiences understand that advertisers have a commercial relationship with a publisher. By wrapping ad messages in a format that looks like editorial content—and calling them something else, such as “sponsored” or “partner” content—they hope to trade on the trust and goodwill editorial has built up with the audience. A bit of confusion is inherent in the appeal.

It’s a tricky trade-off. Publishers would like to see some of that $1.9 billion such ads bring in, but should be concerned about what advertising’s encroachment means for their brands. Already ads have jumped from the right rail into news streams. So-called native ads commonly mimic headline and editorial styles and fonts. Some publications go so far as to enlist their writers to create sponsored posts for advertisers to ensure the right editorial tone is struck. BuzzFeed offers courses to media agencies on its particular brand of storytelling. The line between advertising and editorial is getting really blurry.

Guidance could be on the way, though. Last week the Federal Trade Commission said it would hold a workshop on native advertising in December. The agency wants a better understanding of best practices and whether consumers are able to recognize sponsored content as advertising.

Until there’s a standard for what goes too far, publishers are leaning on their own version of the famous Supreme Court measure for obscenity: “I know it when I see it.” Occasional blunders are inevitable since even the best gut instincts have off days — and the ultimate risk is that such moves result in an outcome that’s bad not just for publishers but marketers, too: jaded, distrusting consumers.

Sponsored content doesn’t have to be pernicious. I have a friend who writes advertorial content at the LA Times, and the work he produces is very similar to the work he did covering arts and entertainment for an alternative weekly in the midwest. Although the events he writes are paying directly for the story, it’s not that different than when the event is paying for a full-page ad adjacent to the story about said event.

Although sponsored content may supplant some of the lost revenue, there remains the question of scale. Most news organizations are local in nature and thus serve a limited audience, while advertising only becomes profitable when scaled to reach enough people.

There have been efforts to create advertising networks to address this challenge, but none of them have demonstrated widespread sustained success. The fact that competing corporations are legally prohibited under antitrust laws from working together to solve the problem is just one of many factors preventing its realization.

But there is one company uniquely situated to build such an ad network. The Associated Press is a cooperative business owned by its member news organizations. Although the AP hasn’t exactly entered the advertising business, the company did sell sponsored tweets during the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show in January.

If the AP were to build its own advertising network, the members that would have the most to gain would be the smaller news outlets that don’t have their online sales team and the traffic to attract national corporations with bigger budgets. And it seems unlikely that these members would have enough clout to catalyze such an endeavor.

Advertising is certainly not the sole solution to this crisis in journalism. As long as the news is filled with natural disasters, crime and crooked politicians, advertising will continue to be a tougher sale than smiling cat videos and pictures of people’s children on Facebook, and even inspiring stories about solving problems of homelessness, crime or poverty will never be as attractive to advertisers as stories about real estate and entertainment. Still, despite the frustrating decline that has left so many news professionals worried about the sustainability of professional journalism, its far too early to completely dismiss advertising.