When faced with daunting subpoenas and the threat of jail time, journalist James Risen did the only thing he could: ignore the uncertain future and keep reporting.

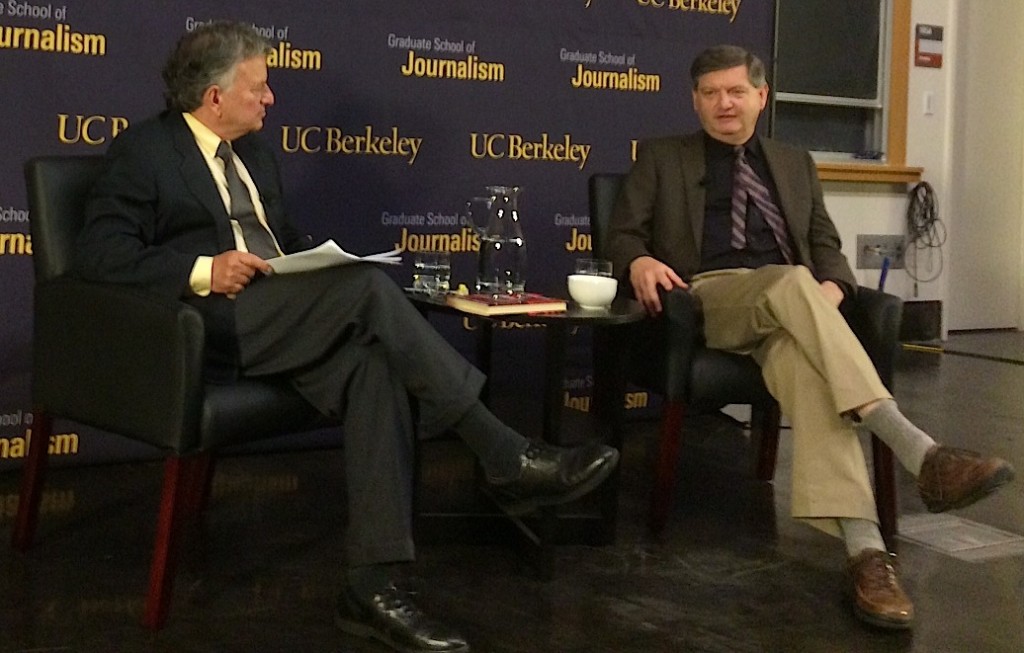

Risen, a Pulitzer Prize-winning national security reporter for the New York Times who is fighting for the right to protect his sources, spoke with Lowell Bergman at an event Thursday hosted by the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Bergman is an investigative journalist and reporter for Frontline who heads up the investigative program at the journalism school.

“It’s just kind’ve become background noise in my life,” said Risen. “Actually its helpful. People now know that I’ll protect my sources and so I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘I’ll talk to you because I know you’ll protect me.’

“It’s just kind’ve become background noise in my life,” said Risen. “Actually its helpful. People now know that I’ll protect my sources and so I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘I’ll talk to you because I know you’ll protect me.’

It’s been almost four years since the federal government first subpoenaed Risen and ordered him to reveal a source he used for his book State of War. After being subpoenaed in January of 2008, Risen filed a motion to quash it on the grounds that he is protected under the reporter’s privilege.

The reporter’s privilege is a principle similar to the one that allows lawyers and priests to avoid testifying in certain situations. It is recognized in some way by almost every state in the country — through either legislation or case law — but there is no federal law to protect reporters from having to testify. In some cases federal judges have recognized the privilege and in others they have said no such protections exist. The Supreme Court has not visited the issue in more than 40 years.

Risen’s efforts to toss out the subpoena initially proved successful, but the government appealed the judge’s ruling and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated it. Now Risen is preparing to appeal that decision to the US Supreme Court. Its decision could create new protections for press freedoms, but it could also have the opposite effect and actually further erode the rights of reporters.

“At this point the status quo is so bad for press freedom that I don’t think we can stop fighting,” said Risen.

A shield law riddled with holes

There is a proposed shield law currently working its way through Congress that would extend the reporter’s privilege in some circumstances, but the bill is filled with exceptions for who and what would be covered under the law. One of those exceptions excludes national security reporting from the law’s protections.

“I’d be open to a shield law if you crafted it correctly, but this one is terrible, said Risen. “The media industry have gone along with it because they think it’s the best that they can get.”

Perhaps Risen’s concerns are warranted.

The Free Flow of Information Act of 2013, which is the official name of the proposed law, describes itself as “a bill to maintain the free flow of information to the public by providing conditions for the federally compelled disclosure of information by certain persons connected with the news media.”

“The problem is that in Washington, no one wants to protect national security reporting,” said Risen. Bergman described an exchange he had with a member of a congressional oversight committee that both supports and challenges Risen’s claim.

“The member of congress looked at me and said, ‘While I’m against giving you a national security exemption to protect your sources, at the same time I want to make it clear that we in this watchdog committee really don’t have the resources to keep the national security apparatus in line. We depend on you, the press,’” said Bergman. “He convinced me – while I was a little amazed by this — that there are members of congress who can actually keep two opposing ideas in their head at the same time.”

Risen said he fears the proposed law could be used to make reporting on national security issues more difficult or even illegal, calling the bill “a backdoor Official Secrets Act.” In the United Kingdom, the Official Secrets Act makes it illegal for journalists to publish information obtained from classified government documents.

“I think it’s tough at this point. I don’t think we’ll get a good law and I don’t think we’ll get a good court decision for quite a while,” said Bergman. “And you’re definitely not getting any sympathy whatsoever from the Obama administration.”

Looking at California’s state shield law

But if reporters stand resolute and refuse to sacrifice their principles for their liberty the government will not be able to maintain the status quo forever.

Bergman pointed to what happened in California after Bill Farr, a beloved reporter for the Los Angeles Times refused to tell a judge which lawyer had violated a gag order in the 1972 murder trial of Charles Manson. The judge held Farr in contempt and locked him up for the duration of the trial that stretched on another 46 days. But Farr’s principled stand resonated throughout the state, and in 1980 the California Shield Law became part of the state constitution. Since then the law has grown stronger through the course of many legal challenges over who and what would be included within its protections.

More recently, a 2006 ruling by the state’s 6th District Court of Appeals expanded the California Shield Law to include protections for bloggers and other citizen journalists. That case, which began in 2004, involved an attempt by Apple to compel the owner of a blog to turn over his e-mail records in order to identify the source of a leak within the company. Although a Santa Clara County Superior Court judge found that the Web site’s owner did not qualify as a journalist under the law, the site’s owner filed an appeal along with more than a dozen legal briefs from news publications and journalism organizations and successfully created a new precedent that stands today.

It’s possible the same course of action could eventually yield similar results in the federal system, but constitutional lawyers doubt the current Supreme Court is likely to establish a reporter’s privilege.

The long fight for a reporter’s privilege

The first version of the Free Flow of Information Act was introduced on the congressional floor in February 2005. At the time, New York Times reporter Judith Miller was in contempt of court for refusing to testify before a Grand Jury but had not yet gone to jail. She was one of a dozen reporters who had been threatened in federal court for refusing to reveal information about their sources, said Virginia Congressman Rick Boucher when introducing the bill.

“The ability of news reporters to assure confidentiality to sources is fundamental to their ability to deliver news on highly contentious matters of broad public interest,” said Boucher. “Without the promise of confidentiality, many sources would not provide information to reporters, and the public would suffer from the resulting lack of information.”

If the government sends Risen to jail, he will be the second New York Times reporter to have been jailed for contempt of court in less than a decade.

“The best way to cope with it — to fight back against the government really — is just to not let it get to you anymore,” said Risen. “What can you do about it except surrender or fight? And I’m not going to surrender.”

Disclosure: I graduated from the Berkeley School of Journalism and participated in Bergman’s class. I also spent several months in a federal detention center after I invoked the reporter’s privilege after being subpoenaed for a Federal Grand Jury, and I was interviewed by Bergman about the experience for the Frontline mini-series News Wars.