Like a malignant tumor, trolling comments can quickly take over online conversations and transform them into a poisonous well of noise and animosity.

Like a malignant tumor, trolling comments can quickly take over online conversations and transform them into a poisonous well of noise and animosity.

That’s partly why Popular Science announced this week that they are turning off comments on their site, but journalism has always depended on an ongoing conversation with its readers, and comments provide a way for anyone to participate.

How can publications provide that opportunity without spending the massive resources needed to police the trolls and spambots who threaten to destroy any meaningful dialog?

Last month, we looked at how the San Francisco Bay Guardian attempted to quell the anonymous inflammatory comment storm by shutting down the feature for an entire week. In lieu of online comments, Editor Steve Jones invited the unknown number of nameless trolls — and the paper’s supporters — to show up in person at a community meeting to express their criticisms and suggested that people consider sending in a signed letter to the editor. Not surprisingly, the trolls stayed home and silently endured the weeklong vacation, and they have since returned.

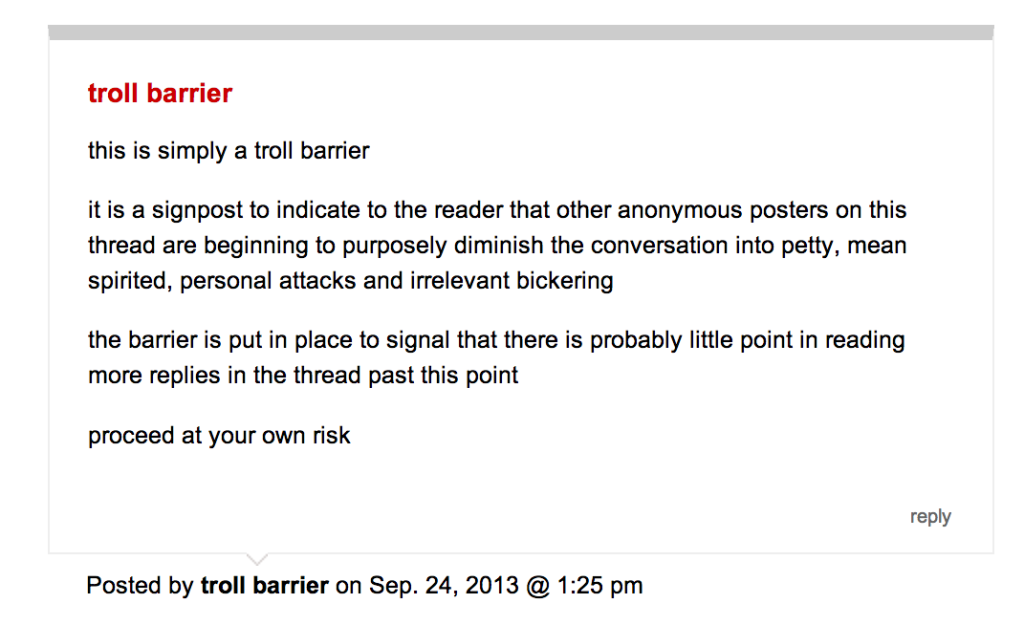

In response, commenter(s) are leaving “troll barriers” to point out comments deemed unacceptable. Unfortunately, since there isn’t an objective standard for what constitutes a troll, the short-sighted solution can resemble the behavior that it professes to resolve.

In response, commenter(s) are leaving “troll barriers” to point out comments deemed unacceptable. Unfortunately, since there isn’t an objective standard for what constitutes a troll, the short-sighted solution can resemble the behavior that it professes to resolve.

When an anonymous individual left a comment on an article about gentrification that expressed support for San Francisco’s changing demographics, it spawned a “troll barrier.” In response, someone using the handle “Chris” pointed out that merely expressing a disagreeable opinion does not constitute trolling.

“This is a discussion forum that the SFBG has chosen to open up to the general public, and posters will express a wide-range of views, some of which I will agree with and some of which I will not,” said Chris in his post. “I absolutely appreciate the idea that racial epithets, LGBT slurs, and other such comments have no place in a civilized public discussion, but comments that one simply disagrees with are simply part of having an open discussion about issues.”

Popular Science shut down its comments after concluding that they may be bad for science. While the suggestion may at first seem far-fetched, Online Content Director Suzanne LeBarre cited research that a field of hostile comments at the bottom of an article can polarize how readers feel about the subject matter of that article. Even “firmly worded (but not uncivil)” disagreements played out in comment threads can impact perception, said LeBarre.

“Because comments sections tend to be a grotesque reflection of the media culture surrounding them, the cynical work of undermining bedrock scientific doctrine is now being done beneath our own stories, within a website devoted to championing science,” said LeBarre in a statement announcing the decision. “Commenters shape public opinion; public opinion shapes public policy; public policy shapes how and whether and what research gets funded–you start to see why we feel compelled to hit the “off” switch.”

At the Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at the University of Texas at Austin, Natalie Jomini Stroud is researching “techniques for engaging online audiences in commercially-viable and democratically-beneficial ways” as part of the Engaging News Project. The project published a report in June that looked at possible ways to mitigate comment incivility. The study looked at how a concluding question will impact the comments generated and also explored what happens when the reporter participates in the comments.

The experiment showed that although concluding with a question for reader may increase the amount of time spent on the page (the results were not statistically significant), it did not generate more comments. But, the research did show that “closed-ended questions, in particular, seem helpful for inspiring civil interactions.”

Some news outlets are attempting to improve civility by requiring people to register and use their own names, said the report. In evaluating the effects of journalist participation in comments, the researchers pulled the data from the Facebook page of a local television station. I imagine that one could expect similar results using Facebook’s Comments Box, which allows anyone to embed Facebook comments (which require an active Facebook account) on their own site.

“The chances of an uncivil comment declined by 15 percent when a reporter interacted in the comment section compared to when no one did so,” said the report. “When the station interacted, it had no effect on the incivility of comments. … It is possible that seeing a recognizable reporter from the news broadcast — as opposed to a generic station logo accompanying each comment — sparked additional civility.”

It looks like Google may soon offer its own way for sites to replace their existing comment systems to one with greater accountability. The company is already changing the way YouTube handles comments, and If YouTube’s new approach to comments proves successful it may soon spread across the Web. With the new system, comments will no longer be shown in chronological order. Instead, they will feature better moderation capabilities to help people maintain civility on the comments for their submissions. Using Google+, comments from any friends or acquaintances will get top billing and be posted to the user’s Google+ page as well. Google+ comments are already available for people using Blogger, and there are even 3rd-party hacks to extend that functionality to other sites.

Of course this solution would require that visitors have an account with Google+, a similar problem to using Facebook comments, and there is no way to have any sort of verified account that doesn’t have the same hurdle.

One possible substitute — which I’ve never heard discussed in relationship to replacing comments — is a live video chat. Would strangers in an online room engage in civilized conversation if they can look each other in the eye?

If requiring real names can improve a forum’s civility, I’m sure seeing their real face would do even more to create an environment where meaningful conversation can flourish.