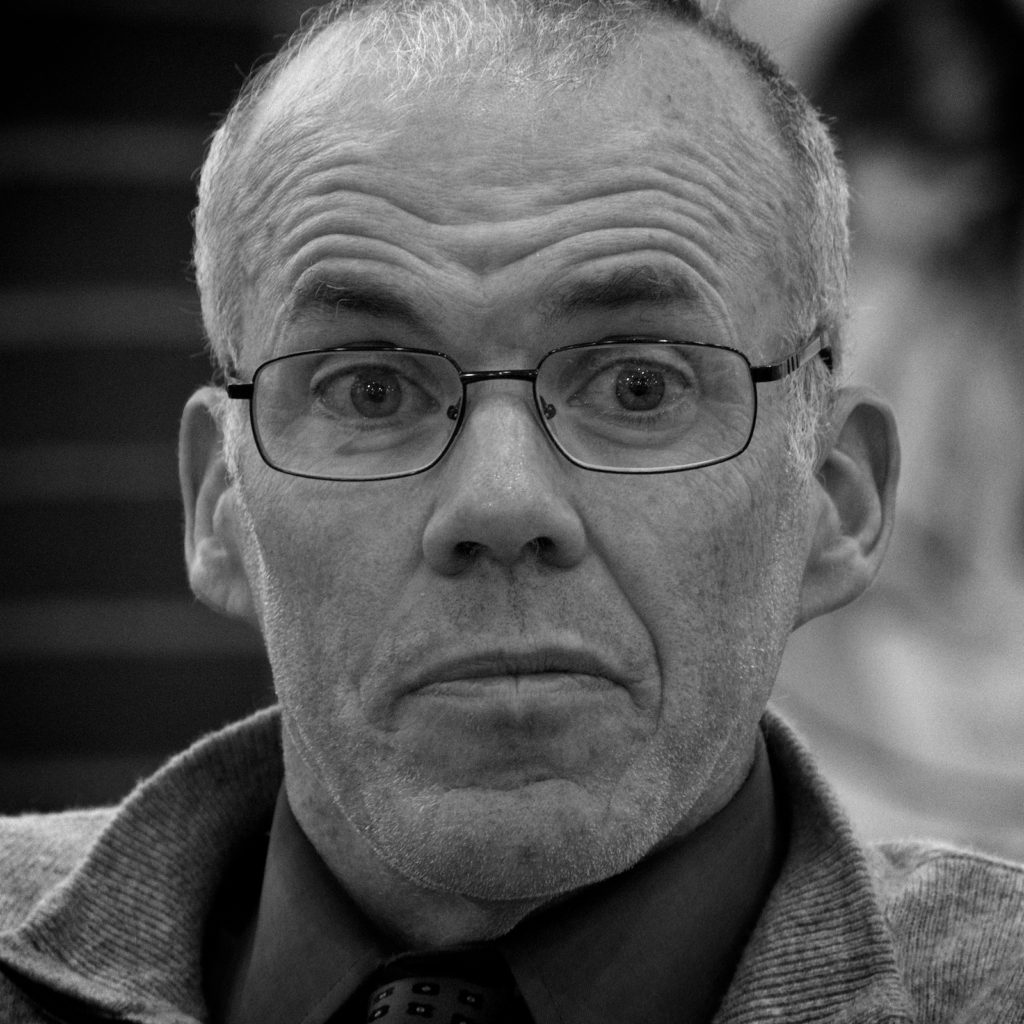

This story reports on a 40-minute speech by environmental activist and journalist Bill McKibben at a conference, “Journalism is Dead; Long Live Journalism,” organized by Journalism That Matters, and following his receipt on Aprl 3, 2013 of the “Anvil of Freedom” award from the Edward W. Estlow International Center for Journalism and New Media at the University of Denver. The full transcription of his speech may be downloaded as a PDF from HERE and an MP3 podcast of the talk is HERE.

(Watch archived video of McKibben’s speech. The first nine minutes has no audio; McKibben begins speaking at 11:30 into the video)

Before he wrote in 1989 the first and most famous popular book about climate change, The End of Nature, Bill McKibben considered himself “a good journalist, and nothing more, for awhile.” But now the climate-change activist, founder of 350.org, is challenging fellow journalists – he still believes he is one – to see climate-change reporting as the ultimate test of journalism’s value.

“I long ago concluded, and in fact I concluded when I wrote The End of Nature that I was no longer in the sense that I was used to thinking about it, an ‘objective journalist,’ ” McKibben said in a 40-minute speech April 3 at the University of Denver. “I knew that I didn’t want the planet to heat up. I had taken sides in this, OK? . . . But it doesn’t mean that I’m not a journalist anymore and completely capable of uncovering new stuff and spreading it out and getting it around and then going in and trying to make it count for something, too, you know?”

McKibben was speaking to about 100 people after receiving the annual “Anvil of Freedom” award from the Estlow Center for Journalism and New Media, at the university. His talk came at the midpoint of a conference organized by the non-profit group Journalism That Matters, entitled: “Journalism Is Dead; Long Live Journalism.” McKibben said climate change will give mankind the opportunity find out whether big brains were a good or bad evolutionary adaptation – as we see how governments and societies deal with the peril.

“We’ll also find out whether the journalistic method was a good idea or not – whether it really works or not,” said McKibben. “Whether it serves the early-warning function we need it to serve or not. In the same way that we found out about how good our military was when it was time to fight World War II. Now we’ll find out how good our journalism is because we’re fighting a war for understand that the stakes and the scale and the pace are absolutely crucial. And those are things we haven’t gotten across and we do have to figure out how to get across.”

McKibben said three numbers – temperature rise, atmospheric carbon and claimed fossil-fuel reserves — prove we have left the 10,000-year Holocene period of geologic history and benign climate stability that underwrote the risk of human civilization. “That’s by far the biggest story and yet in real terms people don’t know it, don’t understand it, don’t get it,” he said. “Somehow, that marks a failure, well, of many things. It’s a great failure of our political system, which I will get to as well. But it is also a great failure of journalists.”

“I think it is probably the single biggest example of a story that, well, we haven’t managed to get right for all kinds of interesting reasons,” McKibben said. As he turned his magazine pieces in The New Yorker into a book, recalled McKibben, “I wasn’t really an environmentalist then. I was mostly a journalist. And I understood, quickly, that this was the most interesting story that there was in the world that this was literally the biggest thing that human beings had ever contemplated doing.”

While climate change as a phenomenon moves far slowly that most stories journalists are used to covering, he says the Earth is now warming 50 times faster than at any point during the Holocene. It moves extraordinarily fast in geological time. That calls for journalists to consider to consider its significance to be as newsworthy as its speed, he said.

“If our job is to tell people about the most important things that are happening in our world so they can act on them, it’s pretty clear that it has been more failure than success. And on an issue with stakes higher than we’ve every faced before. We’re sleep walking off the edge of a cliff, and our early-warning system, which is journalism, has largely failed to alert us to that in ways that matter. Which is not to say there hasn’t been a lot of good journalism done – there has – and I could spent the whole time listing people now who’ve written great books and gret articles, but it hasn’t broken through in the ways that it needs to.”

The “he-said-she-said approach” doesn’t work very well with science because once scientists have reached a working consensus on something, that actually is what you would want to get across, not that there is some very small group who remain doubting, said McKibben.

Nothing excuses failure to get basic facts to public

It is the reality of changes in weather itself, rather than journalism, that has raised awareness of climate change, said McKibben. He said approximately 80 percent of U.S. counties have had a federally declared weather-related disaster in the last two years. “At a certain point,” he said, “People just look out the door and understand what’s going on. Or they look at the things that now we have no choice but to cover and cover intensely.”

Last year, McKibben’s article in Rolling Stone magazine entitled “The Terrifying New Math of Climate Change,” garnered three million “Like” on Facebook, he said, surpassing by far the reaction to the cover-story in the magazine’s issue that month – a profile of celebrity Justin Bieber.

McKibben said he helped found the climate-action group 350.org because that was the number in parts per million of carbon that can be safely sustained in Earth’s atmosphere. He said there are three numbers of importance, the three numbers he laid out in his popular Rolling Stone story.

- The first is two degrees. That’s what the world’s governments and most scientists have said is the most we can safely raise the temperature. “It’s the only thing that the world’s governments have agreed to so it represents the only line that we can kind of hold people to. So it’s an important number,” said McKibben.

- Second number — 565 gigatons — billion tons — of carbon — how much more carbon we can put in the atmosphere and stay below that 2 degree red line that government’s agreed would be catastrophic. “At the rate we’re burning coal and gas and oil at the moment, it will take us about 15 years to blow past that number,” he said.

- The third number – 2,800 gigatons. U.K. financial analysts last year combed S.E.C. filings and annual reports of fossil-fuel companies and found them claiming 2,800 gigatons worth of coal and oil and gas in their reserves – five times as much as the most conservative governments on Earth think would be safe to burn. “But of course they are going to burn it,” McKibben said. “The fact that it is in their S.E.C. reports and their annual-report filings means that is their business plan, right?”

“So once you had those three numbers lined up, then the optics of the whole thing changes. Sudden you realize that the end of the story’s written – there is no room for speculation, or doubt, or wishful thinking. I’ve been covering this for 25 years and I was pretty shocked to see those numbers. Unless we change the script, the outcome is now obvious, inevitable. Written in black ink. And that’s an important thing to know. It is one of the most important sets of facts that we have now in the world. So I was glad to get it out there and glad that it spread quickly. And glad that people understood it.”

McKibben, the journalist, said he found himself with a dilemma. He figured just writing about the problem wasn’t going to make much happen, because of the economic forces at play. “I was a good journalist, and nothing more, for a while,” he said. He continued:

“At a certain point in the course of this 25 years of the global-warming era, it became clear to be that reason was not going to prevail on this issue. That if all it was going to take was scientists going up to Capitol Hill and exclaiming that the worst thing in the world was happening and here’s what we needed to do about it, and the economists coming in right after them and saying, “Yes, and the solution’s pretty simple – put a price on carbon.” If that was going to be enough, it would have happened a long time ago. And instead nothing happened. We had a 25-year, bipartisan effort to accomplish nothing on Capitol Hill, and it continues.”

Twitter; “media we make ourselves” is helping

While journalism may be failing to do its job on climate change, McKibben says the rise of “citizen media,” including such services as Twitter make it inexpensive to propagate important stories through new media forms. He said that was how his 350.org group first raised public concern about the Keystone Pipeline.

The best, at the moment, is when you have this strange synergy of old and new. When you write a piece for Rolling Stone because it is in a place that has a kind of recognizable masthead and credibility, but now it can also circulate online, how you’ve got millions of people who can read it and it can be explosive, said McKibben. “Viralness,” he added, “is really a new thing in a lot of ways for journalism.”

McKibben said such viral new media helps combat what he termed the biggest problem, the biggest dynamic, “that we are up to such a concentration of wealth that it’s basically been able to prevent reason from prevailing. That’s why we don’t get any progress on climate change. That’s why, it’s why even one of Colorado’s two senators voted last week to endorse the Keystone pipeline. Because there’s a lot of money [at stake].”

“But finding out ways, without much money, to be able to stand up to large amounts of money, is in a certain sense what the best journalism has been about almost from the beginning. It’s figuring out how to take power and status quo and put reality in its face and knock it down a peg or two. And so I’m more comfortable than I was when I started with journalism and movements being part of, you know, being intertwined. It’s the natural outcome of good journalism, is to make people care, go do something about something. Especially when the stakes are as clear cut and obvious as they are here.”

Tweets

Covering climate change: Ultimate test of value of journalism? http://bit.ly/10CU12J / Bill

#McKibben issues challenge at#jtmdenverMcKibben to

#jtmdenver Only answer: Join many people into something that has hope of change. Important to cover movement: That’s hopeful.Q from

@calliecarswell to McKibben at#jtmdenver, do we talk about adaptation instead of same story line of climate crisis?

#jtmdenver McKibben: Question: What is the space between denial and despair? McKibben answer: Keep showing examples of solutions underway.Bill McKibben

#jtmdenver /He thinks about 25% of Americans not convincable about#climate change because of either “interest or ideology.”Bill McKibben at

#jtmdenver / dialog with Max@Boykoff on journalism covering climate change / live stream: http://bit.ly/ZajEfEBill McKibben at

#jtmdenver “Now we’ll find out how good our journalism is in fighting a war” to inform the public about the significance.”Bill McKibben at

#jtmdenver / “In this case significance is going to have to supplement novelty as the reason we deal with this issue.”Bill McKibben at

#jtmdenver “It’s the natural outcome of good#journalism to make people care, to go out and do something.”Bill McKibben

#jtmdenver “We are up against such a concentration of wealth that it basicall been able to prevent reason from prevailing.”Bill McKibben

#jtmdenver / “There is now a pretty robust media that we make ourselves.” live stream: http://bit.ly/ZajEfE /

jtmstream

jtmstream